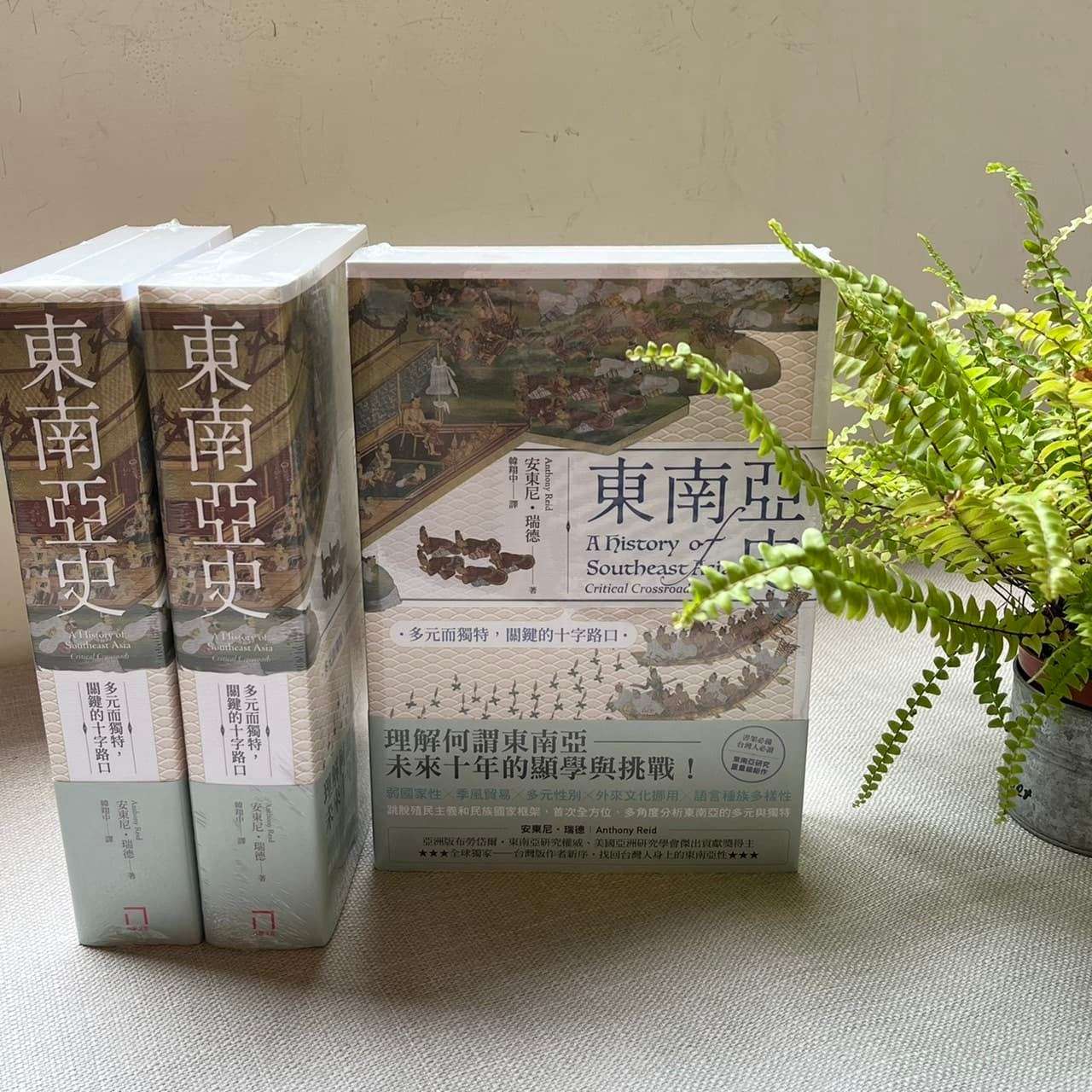

Southeast Asian History: Diverse and Unique, a Critical Crossroads (A Prominent Discipline for the Next Decade, a Classic in Southeast Asian Studies)

Southeast Asian History: Diverse and Unique, a Critical Crossroads (A Prominent Discipline for the Next Decade, a Classic in Southeast Asian Studies)

In stock

Couldn't load pickup availability

出版社: 八旗

ISBN/EAN: 9786267129647

出版日期: 2022-08-10

页数: 624页

语言: Traditional Chinese

—Anthony Reid —

The authority on Southeast Asian history, the Asian version of Braudel,

Winner of the Outstanding Contribution Award of the Association for Asian Studies

★★Published for the first time in Taiwan! The most authoritative classic on Southeast Asian history, a key topic for the next decade! ★★

★★New preface by the author of the Taiwan edition: Rediscovering the Southeast Asian nature of Taiwanese people★★

◆

Weak statehood ╳ Monsoon trade ╳ Gender diversity ╳ Cultural appropriation ╳ Linguistic and ethnic diversity

Southeast Asia is a vast collection that transcends national history

It is a diverse and unique area that can only be described as "Southeast Asian"

Diverse ethnic civilizations and humid jungle waters

Why has Southeast Asia become a "critical crossroads"?

Taiwan is located at the northern gate of a crossroads. How should we communicate with it?

Southeast Asia is neither China nor India, maintaining its uniqueness

Southeast Asia has long been seen as unique by its neighbors: the Chinese called it "Nanyang," the Indians called it "Suwarnadwipa," the golden land, the Arabs called it "Java," and the Europeans called it "Further India" or "India beyond the Ganges."

Southeast Asia, therefore, has always been a unique region of immense diversity—a unique environment encompassing a hot and humid monsoon climate, dense jungles, extensive river systems, and periodic natural disasters such as volcanoes and tsunamis. Due to its fragmented topography and isolated waterways, populations were primarily connected by sea rather than land, preventing Southeast Asia from being unified and governed by large empires. Until the early 19th century, Southeast Asia was perceived by outsiders as a coherent entity, without the concept of nation-states.

Modern Southeast Asia's gene pool and language base largely derive from China to the north, while its religion and written culture originate from India to the west. However, the influence of these two giant neighbors' civilizations on Southeast Asia was limited. Southeast Asia, "neither China nor India," has always maintained its own unique identity. Southeast Asia's location at the crossroads of East Asian migration southward and Westerners eastward led to the arrival of Islamic and European civilizations. These various civilizations, driven by geography, climate, and trade, encountered, converged, and collided here, creating a diverse and splendid Southeast Asian culture and ultimately becoming a crucial crossroads.

From statelessness and weak states to nation-states: Southeast Asia’s millennial transformation

Southeast Asia's earliest societies were characterized by a strong sense of statelessness. These stateless peoples subsisted through gathering, hunting, and nomadic farming, cautiously engaging in trade and exchange with more hierarchical kingships to prevent their subjugation. This statelessness, particularly in the land areas of Southeast Asia (such as present-day Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Yunnan in China), is what the author calls "Zomia" (highland life).

Before the Western concept of the nation-state emerged in the 19th century, Southeast Asia had a weak state concept, best described as "weak state." Two representative political systems were the "nagara" and the "negeri." The former, the "nagara," dominated mainland Southeast Asia between the 10th and 13th centuries, with cities like Angkor, Bagan, and Majapahit on Java. They viewed themselves as the focal points of civilization and the seat of divine kingship, relying on rice cultivation for a secure food supply. The latter, the "negeri," dominated the commercial era from the 15th to the 17th centuries. Similar to port city-states, the most famous of these were Malacca, Manila, and Brunei. These small polities, thriving at shipping hubs, were built on maritime trade, with hosting international traders being their fundamental raison d'être.

The crucial period for the formation of modern Southeast Asian nation-states was the first half of the 19th century. Prior to this period, Southeast Asia had no fixed borders, other than the one separating Dai Viet from China. With the advent of European nationalism, Southeast Asia was integrated into a new world system. The Netherlands, Britain, Spain/the United States, and France drew borders across the region. The introduction of modern education gradually fostered the concepts of national language and nation, leading to nationalist independence movements. The present-day Southeast Asian nations sprang up like mushrooms in the wave of nation-state independence following World War II.

Thus, we can see that the nation-states, national languages, and borders of present-day Southeast Asia are products of the past two hundred years. During this period, the importance of nation, ethnicity, and religion in the lives of Southeast Asians has grown, leading to the fragmentation and division of Southeast Asia, which was once a unified whole. When reviewing the millennia of Southeast Asian history, it is impossible to describe it using known modern borders; doing so would lead to historical misunderstandings. Therefore, the author of this book, Reid, uses geographical units such as islands and watersheds to detail Southeast Asia's complex journey from statelessness, to weak states, to nation-states.

■Only by understanding “Southeast Asianness” can we understand the history and nature of Southeast Asian countries!

Balancing diversity and uniqueness has always been a challenge for Southeast Asia. This book explores the region's diversity and uniqueness, spanning two millennia from ancient times to the present, using this "critical crossroads" as its starting point. If we were to describe Southeast Asianness in the simplest terms, it would be: environment, gender, and a weak state.

◎ “Environment” refers to Southeast Asia’s hot and humid climate, monsoon-swept land, and unstable geological conditions at the junction of plate tectonics

In the age of sailing ships, which relied on wind power for ocean voyages, the monsoon, with its alternating wind direction each year, was very beneficial for ocean voyages in Southeast Asia, making it the cradle of global trade. However, due to its unstable geological conditions at the junction of plates, Southeast Asia was plagued by volcanic eruptions, periodic population declines, and the development of a rice-growing civilization due to the cover of volcanic ash.

Through increasingly sophisticated dating techniques, it has been discovered that large volcanic eruptions can cause short-term fluctuations in global climate. Therefore, Reid believes that Southeast Asia's environmental impact is global, and that violent volcanic eruptions in Southeast Asia are often the culprit for the global Little Ice Age. It is precisely this unique environment that has fostered the diversity of species and civilizations in Southeast Asia, which is the very essence of Southeast Asia's uniqueness.

◎ "Gender" refers to the fact that women in Southeast Asian history have enjoyed the greatest autonomy in human society.

In Southeast Asian countries, property is jointly held by both spouses, with each having financial autonomy. Southeast Asians believe that women should control the family's financial income and manage its finances, and their property rights are adequately protected. Consequently, Eastern and Western traders often entered into short-term marriages with local women to secure trading agency rights.

The dominant position of Southeast Asian women also led to the development of unique sexual services by men, as well as a diverse, transgender culture. Even as Confucianism, Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity introduced foreign models of male dominance to Southeast Asia, these gender relations remained somewhat uniquely Southeast Asian. It wasn't until the arrival of colonialism in the 19th century that the status of women declined.

◎ “Weak state” – refers to the fact that Southeast Asian societies do not have a unified central government and have not developed a bureaucratic state

Southeast Asia has always been characterized by highland anarchy, yet they have nonetheless developed distinct civilizations, such as the self-sufficient rice-growing "Nagara" and the "Negrig"—trade ports at the heart of transshipment. Unfettered by government, Southeast Asian civilizations have become more dynamic, more egalitarian, more trade-oriented, and more diverse.

Southeast Asia is unique and diverse, and Southeast Asian history will become a prominent subject in the next decade.

The author of this book, Anthony Read, is a leading international scholar of Southeast Asia. His research, rather than focusing on the so-called grand events that shaped history, emphasizes the environment, geography, and the daily lives of ordinary people, following the Annales School approach. He is often called the "Braudel of Asia." Furthermore, Read maintains a global historical perspective, emphasizing that the encounter, intertwining, and mutual influence of the forces of India, China, Islam, and modern Europe at this crucial crossroads is a crucial feature of Southeast Asia in global history.

Currently, most Southeast Asian-related publications in Taiwan focus on specific country histories, often with a heavy emphasis on nationalist perspectives. To explore Southeast Asia's 1,300-year history, relying solely on colonialist and nationalist perspectives will fail to grasp its true nature. This is because Southeast Asia did not develop a so-called "political system" until the late 19th century, and "nation-states" only emerged in the mid-20th century.

This book is the first authoritative, comprehensive, and multifaceted analysis of the diversity and uniqueness of Southeast Asia. Rather than following a single timeline from ancient times to the present day, it delves into diverse themes, including climate, trade, religion, politics, and humanities. The focus of the narrative varies from era to era. Even in different eras, Southeast Asia's continental, peninsular, and archipelagic regions are not always continuous and may sometimes overlap, further highlighting the diverse and unique character of Southeast Asia and its history.

Located at the crossroads of Beida, Taiwan is part of the pan-Southeast Asian culture.

Since the 17th century, with the advent of the Age of Exploration, Taiwan has once again become involved in Southeast Asia's maritime network. The author specifically points out that Taiwan Island is the birthplace of a large language family, the Austronesian language family, and that "without Taiwan, there would be no linguistic map of Southeast Asia."

Taiwan's history of a weak state and a strong society is very similar to that of Southeast Asia. In fact, Taiwan has always been part of Southeast Asian culture—the Southeast Asian roots of Taiwanese society and culture are very prominent, not only in the Austronesian languages of its indigenous peoples, but also in the Minnan people, who are important carriers of pan-Southeast Asian culture. Furthermore, like Southeast Asian countries, Taiwan is located within the Pacific Ring of Fire, which is subject to frequent earthquakes and geothermal activity. The culture of its indigenous peoples is both precious and endangered. This is because the Austronesian peoples were similarly treated as a minority by colonizers in their own countries.

Until modern times, Taiwan and Southeast Asian countries have learned from each other, but Taiwan's perspective on the history and future of Southeast Asian society is still "from north to south", viewing the ocean world with a land-based mindset, and even adopting a New Southbound Policy that embraces economic colonialism. Author Reid emphasized that "looking at Southeast Asia from the south to the north is extremely important" - for Taiwanese readers, Southeast Asia is by no means just a superficial New Southbound Policy, but should be viewed through Southeast Asia to see its own past and future. This is the correct way for Taiwan, a maritime country, to connect with Southeast Asia.

Anthony Reid

A leading figure in Southeast Asian history. He holds a BA in Economics and History and an MA in History from Victoria University, New Zealand, and a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge. He is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Royal Historical Society, and a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. He is currently an Honorary Professor at the Australian National University.

After obtaining his doctorate, he first taught Southeast Asian history at the Department of History, University of Malaya. He taught at the Australian National University from 1970 to 1999, and then served as a professor at the National University of Singapore until 2007. He finally retired in Canberra, Australia.

In the 1980s, he chaired the Cambridge Course on Southeast Asian Economic History. In 1999, he went to UCLA to help establish the Center for Asian Studies. In 2002, he received the Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize for Academic Research. He was invited by Wang Gungwu to help establish the Center for Asian Studies in Singapore. In 2010, he received the Distinguished Contribution to Asian Studies Award from the Association for Asian Studies.

He is the author of Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680, The Blood of the People: Revolution and the End of Traditional Rule in Northern Sumatra, and An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and other histories of Sumatra.

Han Xiangzhong

He holds a bachelor's and master's degree in history from National Taiwan University. His translations include "Flowing Frontiers: Yunnan and China in Global Perspective" (published by Baqi Culture Publishing), "City Wall: From the Great Wall to the Berlin Wall, a History of Human Civilization Forged in Blood and Brick," "European History from a British Perspective: From the Glory of Athens to the Rise of Putin, New Perspectives and Humorous Interpretations," "Jung on Psychology and Religion," and "History Hunters: In Search of the Lost Treasures of the World."

Introduction/Article: Zheng Yongchang (Retired Professor of History, National Cheng Kung University)

•Author's Preface

• New preface by the author of the Taiwan edition

Chapter 1 - Peoples of the Humid Tropics

• Good climate, dangerous environment

•Jungle, hydrology and people

•Why is the population so sparse yet diverse?

•Agricultural and modern languages

• Rice Revolution and Population Agglomeration

•The agricultural foundation of the state and society

• Food and clothing

•Women and men

• Not China, not India

Chapter 2 - Buddha and Shiva in the Land Below the Wind

• Debate on Indian nation

• Bronze, iron, and pottery in the archaeological record

• Buddhist world and Sanskrit culture

• Shiva and Nagara in the Charter Era: 900-1300

• The gateway port of Austronesian peoples: Negri

• Dai Viet and its border with China

• The stateless majority in the Charter era

• Crisis of the 13th/14th centuries

Chapter 3 - Trade and Trade Networks

• Land and sea routes

• Specialized production

• Consolidation of the Asian marine market

• Austronesian and Indian pioneers

• East Asian trade system from 1280 to 1500

•Islamic Network

•European

Chapter 4 - Cities and Products Shipped to the World: 1490-1640

• Southeast Asia’s “Business Era”

• Crops for world markets

•Ships and traders

• Cities as centers of innovation

• Trade, Guns, and New Nations

•Business organizations in Asia

Chapter 5 - The Religious Revolution and Early Modernity, 1350-1630

• Southeast Asian religions

• Theravada Buddhism International Circle and Continental Countries

• The Beginnings of Islam: Traders and Mysticism

• The polarization of the First Global War: 1530–1610

• Competing universalisms

• Diversity, religious boundaries, and “highland barbarians”

Chapter 6 - The Encounter between Asia and Europe: 1509-1688

•European-Chinese cities

•Women as cultural mediators

• Cultural hybrid

•Islam's "Age of Discovery"

• Southeast Asian Enlightenment: Makassar and Ayutthaya

• As an early modern form of gunpowder king

Chapter 7 - The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century

• The Great Divergence Debate

• Southeast Asians lost profits from long-distance trade

•Global climate and regional crises

• The political consequences of the crisis

Chapter 8 - Indigenous Identity: 1660-1820

• Eighteenth-century cohesion

• Religious syncretism and indigenization

• Performances in palaces, pagodas and villages

•History, myth and identity

• Integration and its limitations

Chapter 9 - The Expansion of the Sinicized World

• Dai Viet's 15th-century revolution

• The Yue people's "southward expansion"

• The diverse southern frontier of Cochinchina

•Great Vietnam during the Nguyen Dynasty

• Commercial expansion in the “Chinese Century”: 1740-1840

• Chinese people on the southern economic frontier

Chapter 10 - Becoming a Tropical Plantation: 1780-1900

•Pepper and coffee

• Commercialization of major crops

• New Monopolies: Opium and Tobacco

• Colonial oppression of agriculture in Java

• Plantations and haciendas

• Rice monoculture in the continental delta

• Comparison of pre-colonial and colonial growth

Chapter 11 - The Last Struggle for Asian Autonomy: 1820-1910

• Siam: The “civilized” survivor

• Konbaung Burma: Modernization Doomed to Fail

• Nguyen Dynasty Vietnam: The heyday of Confucian fundamentalism

• “Protected” Negri

• An alternative for Sumatran Muslims

• Bali's apocalypse

• Operation "Big Brother" in the Eastern Islands

•The last people to flee the country

Chapter 12 - The Shaping of a Nation: 1824-1940

• European nationalism and the boundaries of art

• “Nushandara”: From multiple regimes to two regimes

•The largest Myanmar, the most complete Siam

• Westphalian system and China

•Build national infrastructure

•How many countries are there in Indochina?

• Nation-building within new sovereign spaces

•State, but not nation

Chapter 13 - Population, Peasantry and Poverty: 1830-1940

• More and more people

• Involution and small-scale farming

• Dual economy and the absence of the middle class

•Subjugating women

• Shared poverty and health crises

Chapter 14 - Modernity of consumption: 1850-2000

• Premises in fragile environments

• The evolution of food

•Fish, salt, meat

• Stimulants and drinks

• Fabrics and clothing

• Modern clothing and identity

•Performance: From festivals to theatre

Chapter 15 - Progress and Modernity: 1900-1940

•From despair to hope

•Education and the new elite

• The triumph of nationalism in the 1930s

• Modern masculinity

Chapter 16 - The Crisis of the Mid-Twentieth Century: 1930-1954

• Economic crisis

• Japanese occupation period

• The Revolution of 1945

•Was independence achieved through revolution or negotiation?

Chapter 17 - The Military, Monarchy, and Marx: The Direction of Authoritarianism, 1950-1998

• A brief democratic spring

•Inherit the gun of the revolution

• Philippine authoritarian style

• Rebuilding the “protected” monarchy

•The Twilight of the Indochinese Kings

•Reinventing the King of Thailand

•Communist authoritarianism

Chapter 18 - The Great Rise of Commerce: Since 1965

• Economic growth finally arriving

• More rice, fewer children

• Open and controlled economy

• Profits and losses

•The cost of the dark side: environmental damage and corruption

Chapter 19 - Shaping Nations, Shaping Minorities: Since 1945

• High Modernism period: 1945-1980

•Education and national identity

• Puritanical globalism

•Join an integrated yet diverse world

Chapter 20: Southeast Asia's Position in the World

•The concept of region

• Global comparison

Share