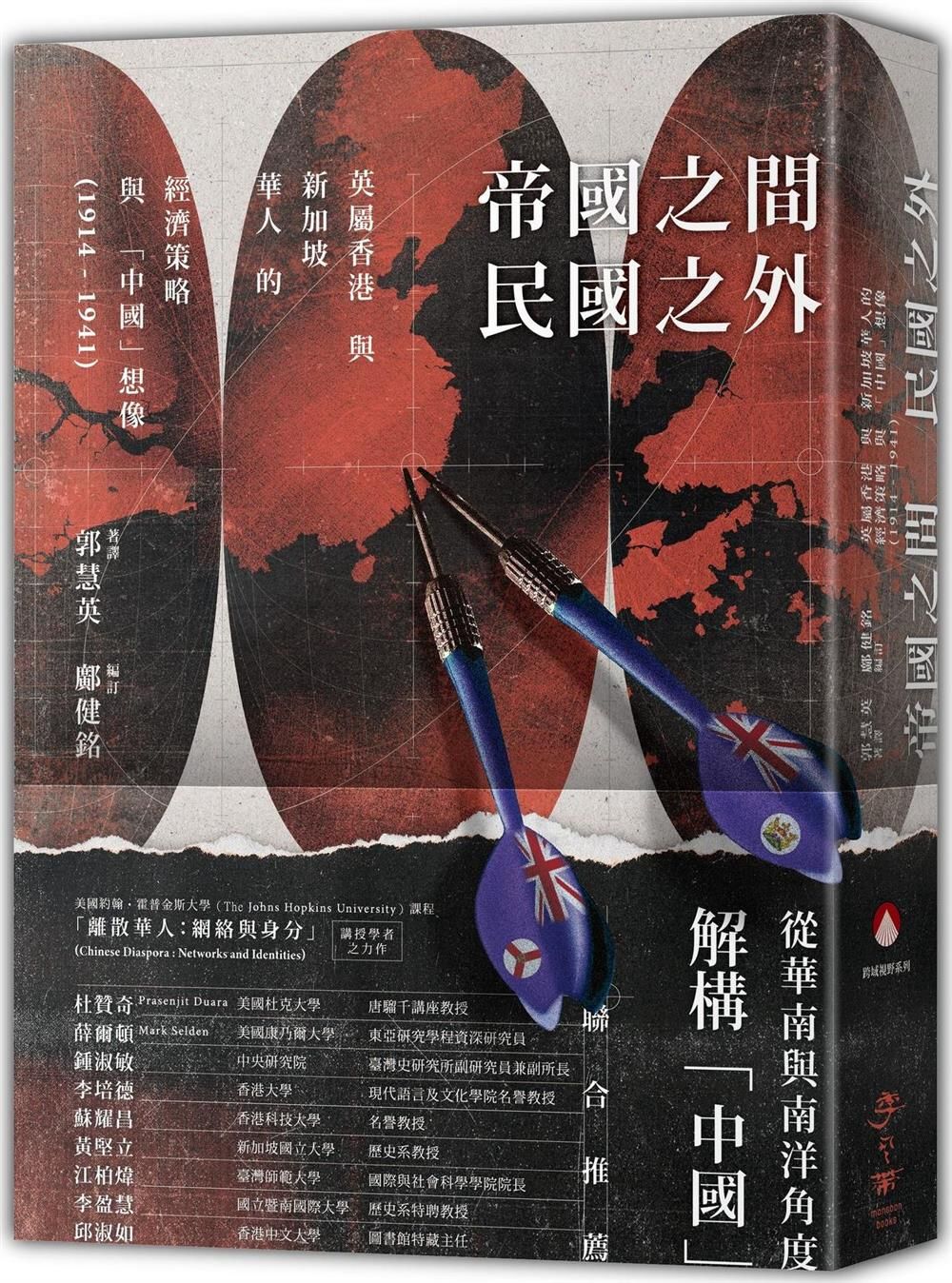

Between Empires, Beyond the Republic: Economic Strategies and Imaginations of “China” among Chinese in British Hong Kong and Singapore (1914-1941)

Between Empires, Beyond the Republic: Economic Strategies and Imaginations of “China” among Chinese in British Hong Kong and Singapore (1914-1941)

5 in stock

Couldn't load pickup availability

出版社: 季风带

ISBN/EAN: 9789869745895

出版日期: 2021-02-10

页数: 540页

语言: Traditional Chinese

• The concept of "Chinese nation" is a modern construct. In modern times, what are the differences in the understanding of this concept between overseas Chinese and mainland Chinese?

• How do the imaginations of “China” differ among the Min, Yue, Chao, and Hakka ethnic groups in South China who have migrated overseas? Why is this so?

• In the early 20th century, what were the different understandings and calculations of the “National Products Movement” by the Nationalist Government in mainland China and even by Hong Kong and Singapore under British rule?

The concept of the "Chinese nation" is not a timeless one. In the early 20th century, political developments in mainland China, British colonial rule in Singapore and Hong Kong, the expansion of Japan's influence in Southeast Asia as a later empire, the varying concerns of South China's ethnic groups emigrating overseas for their respective hometowns in Guangdong and Fujian, and the commercial interests of overseas Chinese merchants affected by the global economic depression all shaped the imagination of "China." Consequently, Chinese nationalism evolved differently within mainland China and among overseas Chinese.

In other words, the rise of Chinese nationalism did not automatically bridge the divides and differences between linguistic groups or unify the national identities associated with various overseas Chinese communities. Before World War II, a pan-Chinese imagined community had yet to fully materialize. Social networks based on dialects, such as those of Cantonese, Fujianese, and Hakka, remained influential, each contributing to a different interpretation of Chinese nationalism. In the late 1910s, mainland Chinese nationalism was anchored in anti-Japanese sentiment; by the 1920s, the British were considered the enemy; and by the 1930s, the Japanese were once again the public enemy. The evolving definition of mainland Chinese nationalism created friction between diverse Chinese business networks, and hometown ties ultimately eroded rather than strengthened Chinese nationalism among overseas Chinese.

In this context, we should re-examine the historical development of the two port cities of Singapore and Hong Kong. In modern times, Singapore and Hong Kong were not simply colonies of the British Empire, nor were they merely undeveloped Southeast Asia, as the Japanese viewed it. The Chinese in Southeast Asia referred to themselves as Huaqiao, and they did not exclusively follow the political leadership of mainland China. Furthermore, Southeast Asia was not simply an extension of mainland China, but rather a distinct political, economic, and cultural space. This space, centered on Hong Kong and Singapore, connected Guangdong and Fujian, while also connecting to the commercial networks of the Japanese Empire (for example, the Kobe-Hong Kong-Singapore commercial network of Cantonese merchants, or the logistics routes from Keelung through Java to Singapore under Japan's Southward Expansion Policy). Furthermore, the commercial corridors of Hong Kong and Singapore served as a confluence of cross-border Chinese merchant activities within trade exchanges and political mobilization across China, Southeast Asia, and the Japanese Empire (including Taiwan). The history of this space is therefore a history of multiple flows.

Today, the mainland Chinese government has increasingly manipulated various flows between China and overseas. How can overseas Chinese preserve their existing diverse and autonomous cultural spaces? Drawing on the historical experience of the early 20th century, preserving South China languages like Min, Cantonese, Teochew, and Hakka, strengthening the local and cross-regional networks of these South China language groups, and maintaining a diverse and autonomous civil society may still be the best answer to official nationalism in mainland China.

Guo Huiying

She holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the State University of New York at Binghamton and both a Master's and Bachelor's degree in Sociology from National Taiwan University. She is currently an Associate Research Professor in the Department of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University. She previously held tenure-track positions as Assistant Professor of Asian History at Rose-Herman Institute of Technology, a short-term Senior Visiting Scholar at the Center for Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, an Adjunct Lecturer in the Department of History at Indiana University, and a Visiting Scholar in the Division of Social Sciences at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Her research projects have twice been awarded the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) Young Scholar Fellowship in Cross-Regional Research (a 2012 postdoctoral fellowship and a 2019 New Paradigm Program grant), as well as the 2016-2017 William-Dearborn Fellowship in American History from the Houghton Library at Harvard University and the 2019 Annual Paper Award from the Institute of Hong Kong Studies at the Education University of Hong Kong. Papers can be found in Nations and Nationalism, Chinese America: History and Perspectives, Translocal Chinese: East Asian Perspectives, Enterprise and Society, Review (Fernand Braudel Center), Journal of Contemporary Asia, China and Asia: A Journal in Historical Studies , Knowledge in Translation (Manning and Owen eds.), Framing Asian Studies (Tzeng, Richter and Koldunova eds.), Race and Racism in Modern East Asia (Demel and Kowner eds.), Chinese History in Geographical Perspective (Du and Kyong-McClain eds.), Singapore in Global History (Heng and Aljunied eds.), etc. Author of Networks Beyond Empires: Chinese Business and Nationalism in the Hong Kong-Singapore Corridor, 1914-1941 .

Preface (New Preface by the Author of the Chinese Edition):

The Origin of Writing Between Empires and Beyond the Republic of China ⊙ Guo Huiying11

Recommendation:

1. Mark Selden (Senior Research Fellow, East Asian Studies Program, Cornell University, USA) 22

2. Professor Prasenjit Duara (Tang Liuqian Chair Professor at Duke University, USA) 23

3. Huang Jianli (Professor of History, National University of Singapore) 24

4. Su Yaochang (Honorary Professor of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) 25

5. Jiang Baiwei (Dean of the College of International and Social Sciences, National Taiwan Normal University) 26

Recommended Preface (I) Challenging the Historical Perspective of Sovereign States: Deconstructing Modern Chinese Politics from the Perspective of Overseas Chinese Business Economic History ⊙ Zhong Shumin (Associate Researcher and Deputy Director of the Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica) 27

Foreword (II) Six Keywords of Between Empires, Beyond the Republic of China ⊙ Li Peide (Emeritus Professor of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Hong Kong) 35

Foreword (III) Overseas Chinese in Multiple Networks ⊙ Li Yinghui (Distinguished Professor of History, National Chi Nan University) 38

Foreword (IV) Examining Modern Chinese Politics from a Broad Spatial and Temporal Perspective ⊙ Qiu Shuru (Head of Special Collections, Chinese University of Hong Kong Library) 42

Introduction:

Whose "China"? — Deconstructing the "China" Imagination from the History of Overseas Chinese ⊙ Kuang Jianming 52

Concept Image 63

Chapter 1 Introduction 71

1.1. Overseas Chinese and Mainland Chinese Nationalism 74

1.2. Deconstructing Chinese Nationalism from a Hakka Perspective76

1.3. Research Keywords: “Overseas Chinese”, China and Overseas Chinese79

1.4. Literature Review: Overseas Chinese under the Nationalist Trend in Mainland China 81

1.5. Research Area and Time Period: Overseas Chinese Business Networks 84

1.6. Nationalism under Transnationalism88

1.7. Restructuring the Singapore-Hong Kong Relationship91

1.8. Summary of each chapter 94

1.8.1. The First Perspective: The Shift of Hegemony in the South China-Nanyang World Economic Zone in the Early 20th Century 95

1.8.2. The Second Perspective: State Construction in Modern China 96

1.8.3. The Third Perspective: Cross-Border Networks and Local Identity 97

Chapter 2 Overseas Chinese before the formation of nationalist thought in mainland China 103

2.1. South China as China’s Internal Political Frontier and External Economic Core105

2.2. The Global Economic System and the Role of Overseas Chinese in the Sixteenth Century 108

2.3. From Chinese in South China to Chinese in the Southeast Asian Colonies 113

2.4. The Chinese in the Eyes of British Colonial Officials120

2.5. Foreign Powers, Reform, and Revolution 127

2.6. Overseas Chinese Nationalism 133

2.7. The Chinese in Hong Kong and Singapore 135

2.8. Conclusion 151

Chapter 3: “Enemy” and “State” in the Overseas Chinese World in the 1920s 155

3.1. The Chinese Anti-Japanese Wave in 1919157

3.2. Rice Famine and Anti-Japanese Activities in Hong Kong and Singapore 163

3.3. Overseas Chinese Businessmen and Japan’s Southward Expansion 167

3.4. “Enemy” in the Anti-Imperialist Movement (1921-1924) 172

3.5. Guangdong-Hong Kong General Strike: Political and Economic Struggle between Guangdong and Hong Kong 178

3.6. Hong Kong Chinese Business Leaders During the Guangdong-Hong Kong General Strike186

3.7. Resolving the Conflict between Guangdong and Hong Kong 191

3.8. British Imperialism and Chinese Businessmen in Singapore in the 1920s

3.9. Conclusion 205

Chapter 4: Saving the Nation through Industry: The Interpretation of Chinese Nationalism in Singapore and Hong Kong in the 1930s 209

4.1. The Rise of Tan Kah Kee: A Legendary Chinese Nationalist in Southeast Asia 212

4.2. Between Guangdong and the Nanjing Government: Capitalist Nationalism of Hong Kong Chinese Businessmen (1929-1937) 227

4.3. The Kuomintang’s nationalist propaganda and the response of Hong Kong’s Chinese businessmen (1937-1941) 235

4.4. Conclusion 242

Chapter 5: The Correspondence of Singapore and Hong Kong Chinese Businessmen during the Global Depression 245

5.1. Business Pressures Faced by Chinese Singaporeans During the Global Economic Depression 246

5.1.1. Singapore Rubber Manufacturing Industry 247

5.1.2. The British-Japanese Cloth Sales War in Singapore 258

5.1.3. Trade between Fujian Tea and Japanese Tea in Singapore 262

5.2. Restructuring of Power within the Hong Kong Chinese Business Community264

5.2.1. Eurasian Trade and Chinese Compradors 267

5.2.2. Trans-Pacific Trade, North-South Lines, and Jinshanzhuang 269

5.2.3. Structural transformation of the department store industry 277

5.3. Conclusion 280

Chapter 6 What are the “Interests of the Chinese Nation”? Mainland China, Singapore, and Hong Kong under the National Products Movement 285

6.1. Economic Nationalism in Mainland China during the Nanjing Government Period 286

6.2. The Nanjing Government’s National Products Campaign 291

6.3. The New Port Commercial Corridor under the National Products Movement in Mainland China 298

6.4. Bottom-up integration of Shanghai and Hong Kong during World War II 309

6.5. Economic Explanation of the Effectiveness of the Anti-Japanese Goods Movement 312

6.6 The Development of Light Industry in the Frontiers of the British Empire 325

6.7. Conclusion 337

Chapter 7: The Split “Chinese Nation” Consciousness: “New Fujian,” “New Guangdong,” China, and New Hong Kong 341

7.1. The Nanjing Nationalist Government and the “Overseas Chinese Hometown” 343

7.2. Fujianese in Southeast Asia and the “New Fujian” (1933-1934) 349

7.3. Hong Kong and “New Guangdong” 353

7.4. Commercial Relations between Southeast Asia and China under the Nationalist Government’s Controlled Economy (1934-1941) 359

7.5. Overseas Chinese Nationalism during the KMT-CCP Split

7.6. Conclusion 374

Chapter 8 Conclusion - Overseas Chinese Narratives Outside Mainland China 379

8.1. Patriotic Overseas Chinese from the Perspective of the Republic of China 382

8.2. Overseas Chinese outside the Kuomintang 384

8.3. Overseas Chinese in the Sunset of the British Empire 389

8.4. Different interpretations of imagined communities 392

8.5. “Gangs” within the “State”: Mainland China and Overseas Chinese (I) 394

8.6. “Gangs” within the “State”: Mainland China and Overseas Chinese (Part 2) 395

References 402-442

Notes 443-539

Share